所在位置:首页 > 贸促动态 > 市长国际企业家顾问会议 > 往届回顾 > 第九届顾问报告 > 正文

Sharing Best Practices for Building Beijing Into a World-class City

2012年05月23日 来源:中国国际贸易促进委员会北京市分会

Introduction

Urbanisation is now at the forefront of globalisation, as cities have become the centres of global economic growth. More than half of the world’s population is now living in cities, and in the next 40 years, by 2050, the global urban population is expected to rise to 70 percent. Much of that urban growth will occur in developing countries. With one of the fastest growing economies the world has seen, China will also witness one of the fastest increases in its urban population, growing from the present roughly 42 percent to 70 percent in 2050.

We are therefore now experiencing our first urban century, redefining how we shape our cities and revamping how we treat the world. Urban development and governance are becoming more important than ever before to ensure sustainable economic growth and the overall quality of life.

As China’s capital city, Beijing and its development, especially during the past decade, have presented a shining example of what is possible. Clear government policies and effective implementation, coupled with the successful staging of the 2008 Olympic Games, have guided the city of more than 17 million people to make impressive strides in a very short time.

In the six years from 2001 to 2007, Beijing achieved an annual average growth rate of 12.4 percent, while more than doubling the per capita GDP of its residents. The economy expanded through various new growth sectors, such as: hi-tech; finance; and tourism, while transportation links were further extended, adding a total of more than 200 kilometres of subway and light rail. Other infrastructural and architectural assets were also dramatically upgraded, both in aesthetic appeal and practical function. Altogether Beijing’s impressive economic and infrastructural developments have significantly improved the quality of life for its residents and made for one of the most compelling urban development stories in recent history.

The next stage of development continues with a further grand vision, which the Municipal Government has effectively set out in the form of a broad framework and timeframe. During the current Phase I, Beijing aims to lead the country in establishing the solid foundations and structures of a modern international city. Phase II, targeting a 2020 completion, aims to achieve the comprehensive modernisation of the city with all its unique features. By 2050, during phase III, Beijing endeavours to put in place the essential economic, social and environmentally sustainable components, aspiring to achieve top status as a truly world-class city.

This paper outlines the common principal factors that constitute a prototypical world-class city and highlights some of the characteristics that have emerged in recent years to help define “world-class”. In context, the paper will also share best practices of the City of Manchester on the government’s role in leading a city towards world-class status.

PART I – World-class Cities: The Building Blocks

In an era of globalisation, the activities and decisions taking place in world-class cities have the ability to dictate trends, actions and decisions elsewhere, with an immediate and material impact on global affairs. It is where the world’s problems are identified, solutions found and goals advanced.

World-class cities have been powerful driving forces of human and social progress since the start of civilisation. Athens, Alexandria and Rome have each defined that classification at different points in history but have since, with the passage of time, become less relevant. Today’s top world-class cities include New York, London, Paris and Tokyo, according to the general consensus among the world’s leading studies focusing on the topic.

Annually, a number of reports focus on the topic of cities, employing varying sets of factors to arrive at slightly different conclusions. The Globalisation and World Cities Study Group and Network (GaWC), part of the Loughborough University in the UK, was among the very first to attempt to define, analyse and rank the world’s major cities, according to their level of world integration. Other studies include the widely-known “Liveability Ranking” published annually by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), and the “Global Power Cities Index”, gathered by the Institute for Urban Strategies at the Tokyo-based Mori Memorial Foundation, surveying factors such as economy, liveability, ecology and natural environment.

The magazine Foreign Policy led a collaboration that put together the “Global Cities Index”, an in-depth effort at defining and ranking cities. (In the 2008 index, the most recent edition, Beijing ranked No. 12 overall and No. 7 in the category of political engagement.) Most recently, in March 2010, Knight Frank published a “World Cities Survey” as part of its Wealth Report 2010 – Beijing ranked No. 9 overall and No. 4 in political power (the latter rising from No. 7 in 2009).

All these reports arrive at different city rankings but consider a generally common set of features that, once filtered down, can be summed up in three principal characteristics that go to define the world-class city (also called “world city” or “global city”): economic; political; and cultural influence. There is no hard science or formula in qualifying a world-class city, but the process itself helps reveal some of its key building blocks.

Economic Influence

World-class cities are the focal points where activities of national, regional and international significance take place, and in a world whose markets are intimately interconnected, business and economics have become the rule of the game. As such, a city is judged to be of world-class stature based on a mix of factors determining the strength of its business activity – including the total value of capital markets, number of head offices of Fortune 500 companies, and overall volume of goods and trade.

Cities that fulfil these and other qualifications at an optimal level also attract the brightest people, minds and talent, while offering the infrastructural, transportation and logistical capabilities to manage the necessary resources for efficient production and trade. In an age where information has become another critical currency, the breadth and efficiency of their telecommunications networks have become ever more crucial to an economy’s development.

Equipped with such attributes, these cities are the engines of economic growth for their respective regions and countries. Home to top talent in various business sectors, they are incubators for new products, ideas, designs, technologies, services and enterprises. They are where strategic decisions on large-scale production, investment and trade are made, acting as gateways to the flow of resources in and out of the country and neighbouring regions.

Political Sway

Political influence remains no less important. World-class cities typically reside in countries that are already influential players among their neighbours and the world, so their importance becomes magnified in the global geopolitical realm. They are the location of choice for embassies, consulates, major international organisations and top-level political conferences, all helping to link the city with the world, and vice versa. The effects of important global events on one nation or region begin and end with the world-class city.

These cities also have the ability to influence policy on a national, regional and international level by capitalising on their superior advantages in resources, people and overall economic wealth to take the lead on key issues. When they are not making the decisions that impact other countries, they are setting the tone for dialogue, effectively playing a pivotal part in forming the regional or global agenda.

Cultural Impact

The cultural influence of world-class cities, while less traceable, can be equally impactful. For some time already, these cities have been playing a far-reaching role in the economic and political arenas; they were not built overnight. Such influence has also granted them each the privilege of sculpting their nation’s cultural agenda, which is then shared with the world.

The cultural wealth of a country – as experienced through its art, education, literature, music and film – is created, assembled and packaged in major urban centres over generations, weaving the cultural fabric. That wealth can be found in the museums, historic landmarks, theatres, schools and universities, libraries and concert halls, all of which symbolise the city’s influence. The world-class city becomes the bridge for cultural exchanges through its sophisticated trade and political channels. It enables its national heritage to interact with that of other countries, as it incorporates theirs into its own.

PART II – New Features of the World-class City

Major changes on a global scale have been the reliable constant so far this century. The urban transformation, discussed at the start of this paper, has become a major driving force; the global economic balance has started shifting from the West to the East; and tackling climate change has risen to a top priority for governments and businesses alike. In fact, HSBC believes that climate change is the single biggest environmental, social and economic challenge humanity faces this century and has, therefore, made climate change a focus of our sustainability efforts.

The Key Components of Sustainability and Liveability

These recent changes mean that world-class cities of the 21st century will differ from those that developed during the 19th and 20th centuries. These cities will have the same scale of influence, but that influence will arise from a wider scope of priorities. The focus on sustainability, for example, has expanded the goal of pure economic growth to encompass key considerations such as environmental and social responsibility for city policymakers and enterprises. Take HSBC, for example, which operates a global business according to the highest standards of corporate sustainability. This involves managing our own environmental impact and the indirect impact we have on society and the environment through our lending and investment activities.

Sustainability has a direct impact on liveability, another recent feature to define urban world-class status. The natural conditions of the city and its immediate surroundings affect the quality of life of its residents. The basic supply of clean air and water, in addition to quality healthcare, help determine the health of local communities. Policy directions can play a positive role, such as China’s move to limit entities with high-energy consumption and high pollution levels; the implementation of eco-friendly codes on building renovations and new construction; and the availability of urban green space.

For some time sustainability and liveability have been on the agendas of top cities worldwide only as an implied goal, behind political stability and economic development. Now, however, they have risen to the top of the priority list. These two new features are placing greater and wider demands on urban governance, requiring a vision of long-term development, with a real focus on its effects on our surroundings and way of life.

Building on Momentum – Beijing’s Opportunities

By making rapid progress in urban development over the last two decades, Beijing achieved a feat rarely seen before in other major cities. The outcome of clear policies and initiatives culminated in the successful staging of the 2008 Olympic Games, which helped close the gap in the world’s understanding of the capital city and of China at large. This grand event also offered a view into the significant government efforts taken to create a “Green Olympics”.

The chairman of the International Olympic Committee Marketing Commission, Gerhard Heiberg, acknowledged this by saying, “The look of the city has changed a lot since 1974 when I visited Beijing for the first time. Today's Beijing is much greener than it used to be and the living environment has improved significantly.” Already an epicentre of global events, Beijing has not only established its strong economic, political and cultural foundations, but also taken a leap towards dramatically improved surroundings and an upgraded quality of life.

The next stage of development presents Beijing with a timely opportunity to sustain that momentum as it continues to incorporate key features of sustainability and liveability. During this process, the experience of the City of Manchester in the United Kingdom is worth noting, as it highlights the role of city leaders in implementing successful urban regeneration and in attaining world-class ranking for their city.

PART III – The Experience of Manchester: Sustainable Regeneration

Over the past decade, Manchester, located in North West England, has been widely recognised for its sustainable urban regeneration programme, largely credited to the leadership and strategy of its city government.

Manchester recently surpassed London as the most liveable city in the UK, according to the 2009 Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) global liveability survey. At No. 46 overall, it ranks five positions above London and stands tall in the top-third of 140 cities surveyed worldwide. The annual study examines more than 30 factors in five broad categories comprising of: stability; culture and environment; healthcare; education; and infrastructure.

Overall, Manchester is now considered “the second city” of the UK. The Greater Manchester Urban Area, comprising of the city and surrounding areas that spread out from it, is among the largest metropolitan areas in the UK.

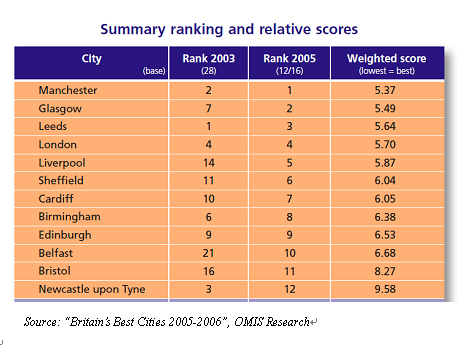

Several other studies of cities have rated Manchester at or near the top. Manchester is also one of the most business-friendly cities in the UK, selected as the best city to do business by “Britain’s Best Cities 2005-2006”. (London placed fourth on the list, below.) The study, conducted by independent consultancy, OMIS Research, reveals the results of an in-depth poll of major employers, looking at key business issues, including labour, taxation, regulation, costs and infrastructure.

Furthermore, Manchester was rated the UK’s second-most business-friendly city for two consecutive years (2007 and 2008) by the “UK Cities Monitor”, conducted by Cushman & Wakefield, the global real estate services firm. The study gathers the responses of senior executives on 21 factors ranging from transport links to staff resources to quality of life. In 2008 Manchester performed particularly well in the following areas:

- The preferred choice of executives as a new headquarters location;

- The preferred choice of executives as a new back office function; and

- Ranked first as the city doing the most to improve itself and the city doing the most to promote itself.

In fact, the variety and scope of high marks received by Manchester in recent years is a true testament to what many observers have called the “visionary” efforts of the city’s leaders. They recognise the achievements of a government, the Manchester City Council, that has devised an urban regeneration strategy for a city that just one decade ago, prior to the recent accolades, was considered to be heading towards decay.

A Former Urban Power in Decline

Manchester’s glory days as a vital commercial centre ended almost as dramatically as they began. The city is considered to be the first industrialised city, developed during the first half of the 19th century, in the Industrial Revolution. Its cotton processing and trading fed the textiles boom, fuelling the rise of other industries, such as general manufacturing, banking and insurance, chemical dyes and transport. Rapid urbanisation was an outcome of success, but most of all, Manchester had clearly established itself as a world-class powerhouse. Its industrial prowess peaked in 1913, when 65 percent of the world’s cotton was processed in or around Manchester.

However, its industrial production suffered major interruptions with the subsequent onset of major world events – the Great Depression and the two World Wars – sowing the start of Manchester’s steady decline. Shifting national policies, evolving economic trends, and rising global competition from the 1960s through the 1980s further contributed to the downturn. Then came what is known as the Manchester bombing in 1996, the terrorist act engineered by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) that struck at the heart of the city – injuring hundreds of people, destroying several buildings and incurring total damages exceeding GBP50 million.

This calamitous event crushed the spirit of the once-proud city, but it also spurred its rebirth. Investments began to flow into Manchester to assist and rebuild in the aftermath of the bombing, and the XVII Commonwealth Games in 2002 would stand as a beacon for the city’s regeneration.

The City’s Vision and Strategy for Regeneration

Manchester’s most recent turnaround, following the gradual inexorable decline, traces its origins to the Manchester City Council, which in 1999 formally laid out its vision for the city’s regeneration. First, it made a decision to focus on East Manchester, an area that was most directly impacted by the city’s decline since the 1960s. It suffered a 60 percent job loss in the traditional manufacturing sector from 1975 to 1985; a 13 percent decrease in population during the 1990s; and nearly 20 percent of properties were vacant, leading to a collapse of the housing market. There was an increase in crime and a crash in income levels – more than half of the residents were receiving some form of government benefit.

Faced with the daunting challenge of rebuilding the city, the Manchester City Council turned its holistic vision into an ambitious long-term programme called the Strategic Regeneration Framework, outlining a comprehensive spectrum of initiatives. While aiming to regenerate the city’s economy at large, it customised targets and solutions to focus on specific areas of need – from education to the environment and from housing to sports and entertainment.

The programme was launched in 2000, setting a general timeframe of 10 to 15 years with ambitious targets, including the following :

- Nearly 2,000 hectares (20 sq. km) of land planned for regeneration

- Attract GBP2 billion of total investments

- Create more than 15,000 new jobs

- Build 12,500 new homes

- Refurbish 7,500 existing homes

- Double the local resident population

To achieve these targets, the Manchester City Council also set up Urban Regeneration Companies (URCs), partnership initiatives aimed at capitalising on the respective advantages of public and private resources and expertise. The City Council was a leading partner in URCs, which also engaged regional and national authorities alongside private enterprises and major community groups. However, they operated as independent private ventures with their business objectives usually focused on rebuilding a designated part of the city as much as on revenue growth.

The City Council established the URCs with the fundamental thought of helping the city help itself, assembling the efforts of its stakeholders with shared interest in rebuilding Manchester. The partnership model was a prominent driving force behind the City Council’s urban regeneration strategy and ultimately its success. Based on the Manchester experience, more than 20 URCs have been created across the UK since 1999 with similar structure, vision and objective towards urban regeneration.

Realising the Vision Through Implementation

The success of Manchester’s regeneration programme is credited to the leadership of the Manchester City Council in setting up URCs like the New East Manchester Ltd. (NEM) partnership, one of the first three URCs established back in 1999. The City Council played an integral role in guiding NEM’s partners towards the stated objectives of the Strategic Regeneration Framework.

NEM embarked on the Strategic Regeneration Framework in 2000 to carry out the programme’s implementation. And although Manchester was bypassed in earlier years in its bids for the 1996 and 2000 Olympic Games, NEM was further given the opportunity to capitalise on the XVII Commonwealth Games held in Manchester in 2002, an event that helped push efforts towards realising the strategic framework.

In 2006 NEM commissioned an interim evaluation by an independent group from the European Institute of Urban Affairs at Liverpool John Moores University; the study applauded NEM as “a very good example of a truly comprehensive urban regeneration company.” Much as planned, NEM managed to attract an average annual investment of GBP200 million in the five-plus years since 2000, a figure that matched the original target well. NEM made effective use of that funding, from both public and private sources, in a number of areas. Highlights include:

- Housing: More than 3,500 new homes completed with another 6,000 in the pipeline (targeting 12,500 homes total after the framework’s first 10-15 years);

- Employment: More than 3,000 jobs created; overall 10.5 percent increase in jobs in the area, surpassing citywide, regional and national trends; unemployment rate decreased from 14.2 percent to 5.7 percent;

- Central Business Park: Phase I completed, covering 182 hectares (1.82 sq. km); a key tenant, Fujitsu UK, took up 175,000 sq. feet (16,258 sq. m) of floor space; Phase II is in progress, covering 145 hectares (1.45 sq. km); and

- Education: Closed the performance gap of East Manchester schools versus those in North West England from 28.9 percent (2001) to 12.8 percent (2005).

The evaluation concluded that, while much remains to be done, NEM’s work in East Manchester has been effective in achieving the targets first set out in the framework. Most importantly, the outcomes were closely measured against the original objectives by employing specific details and figures. The evaluation further stated: “NEM provides many important lessons about the processes, people, politics and powers that are required to achieve successful urban regeneration.”

Leadership and Guidance of City Government

The leadership of the Manchester City Council has been the key driver all throughout the city’s regeneration. It first began with a grand vision of regeneration, but then it clearly identified individual problem areas to better focus on their needs and helped to channel the available resources based on the most suitable strategy. In forming URCs like NEM and with the partners’ support, the Council guided projects that continue to realise the city’s regeneration today.

Manchester’s regeneration has already achieved outcomes that many would not have believed possible just one decade ago. Its vision, strategy, then guidance as part of NEM, have led to the rebuilding of the city’s “hardware” – in the form of much improved housing, retail venues, historic landmarks and sports and entertainment facilities – while upgrading and refining “software” aspects, such as education, healthcare, parks, rivers and overall natural surroundings.

Many of these improvements have been driven with a larger focus on sustainability. Even with its growing commercial power and revived industries, Manchester today is a far cry from the highly polluted city that was once the world’s industrial centre. Still, sustainability has not only been realised in the environmental sense, but also in the business and economic sense. The City Council continues to maintain existing regeneration partnerships while establishing new ones with new areas of focus.

The success and continued progress of Manchester’s regeneration are helping to rebuild the city’s confidence. Moreover, they are benefiting its residents by dramatically raising their quality of life and the city’s overall liveability with the added benefit of attracting continued investment and talent, while improving its ranking among world-class cities.

Conclusion

Urbanisation is an unstoppable global force, as cities are now home to more than half of the world’s population – a proportion that is continuing to grow quickly. In the face of the new challenges of the world today, world-class cities are expected not only to influence the economic, political and cultural realms on a global scale, but also to assume leadership in sustainable development and urban liveability.

Furthermore, leaders of world-class cities have the added responsibility of nurturing platforms where governments, markets and business can effectively work together to tackle these challenges. The experience the City of Manchester offers is a reassuring example of how joint efforts can deliver sustainable solutions and advance the city's standing among world-class cities.

Beijing has made impressive strides in recent years, as its effective governance has transformed many aspects of the capital city. To achieve its goal of becoming a truly world-class city by 2050, Beijing is well prepared to rise above and beyond just economic, political and cultural influence. As shown by the huge success of the 2008 Olympic Games and its green credentials, Beijing has every opportunity to fully realise sustainable development and urban liveability in the coming decades.

主办:中国国际贸易促进委员会北京市分会

建设运维:北京市贸促会信息中心

京ICP证12017809号-3 | 京公网安备100102000689-3号