所在位置:首页 > 贸促动态 > 市长国际企业家顾问会议 > 往届回顾 > 第九届顾问报告 > 正文

The services sector and innovations as drivers of growth in China and Beijing

2012年05月23日 来源:中国国际贸易促进委员会北京市分会

Dr. Josef Ackermann Chairman of the Management Board and the Group Executive Committee

Deutsche Bank AG

Introduction

The global crisis was an event without precedent in recent decades. Every country – even China – felt its impact. Economic growth in China in 2009 declined significantly compared with the very high growth rates achieved in the years prior to the crisis, which culminated in a 13% yoy increase in 2007. Still, growth remained at a robust 8.7% last year and is likely to surpass this mark in 2010 and 2011. Chinese growth is mainly led by investment, much of it directed towards export-oriented production, which is reflected by the fact that the country recently became the world’s new “export champion”. While this economic model has proved very successful, helping to improve the livelihoods of millions of Chinese citizens and supporting regional and even global growth, the sharp fall in international trade in Q1 2009 brought into sharp relief the vulnerability of any growth strategy based mostly on exports. The persistence of global imbalances as well as concerns on the fiscal health of some developed countries poses some risks for a robust and sustainable recovery in external demand. China is thus faced with the challenges of rebalancing its growth drivers.

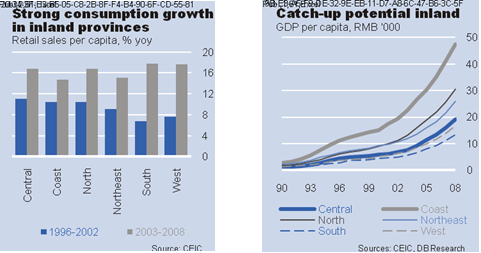

The central government had indeed already looked into diversifying the sources of GDP growth long before the global crisis, namely, in the 11th five-year plan from 2006. In that vein, a major initiative that was put in place is the development of the economic potential of China’s interior. In the inland provinces there is high pent-up demand and incomes are beginning to rise more quickly as manufacturing industries move their production sites away from the coast and generate new job opportunities in the west. Thus, there is huge potential for domestic growth in these areas.

Besides this geographical expansion of economic potential, China could profit from an expansion in the scope of domestic demand, namely, the development of the services sector – both consumer and business services – as complement to the production of goods. The services sector comprises two main sub-sectors: consumer services and business services.

Consumer services are typically labour-intensive, which means that this transition would also create a large amount of jobs. This would allow China’s economy to grow from domestic sources in a more sustainable manner and make it less prone to a weak global economy. Aside from these consumer services there is also large potential for more capital-intensive, high value-added business services as the range of goods produced in China expands. Production of more complex commodities often needs more supporting business services like logistics, R&D or IT.

Finally, a revamped economic growth model should incorporate innovation as a key element. Innovation leads to more efficiency in production processes and thus increases productivity.

The rest of this essay will explore the key drivers of a services- and innovation-led economy from a general perspective and, where possible, applied to the China and Beijing context.

Section 1: Transition into a services economy

1a) Drivers for tartarisation

There are a number of drivers responsible for structural change and the transition from an industrial to a services economy. First a rising share of services in GDP is a reflection of growth and higher per capita income. As households grow wealthier, a greater share of disposable income is being spent on non-essential goods, the majority of which tend to be services.

Second, there is outsourcing. Globalisation compels companies to tap efficiency potentials in order to meet the challenges of worldwide competition. This applies mainly to manufacturing companies. In response to increasing competitive pressures companies outsource supporting activities like IT or logistics services to specialised external providers. This vertical disintegration allows companies to focus on their core competencies and increase efficiency. Thus, globalisation drives tartarisation by causing an intersectional division of labour and increasing demand for business services. To a certain extent this is merely a statistical artefact, though:

After the process of outsourcing a service from a manufacturing company to an external provider the value-added pattern remains – apart from the efficiency gains – virtually unchanged; it is only assigned to a different sector of the economy. Services themselves are only tradable to a limited degree and international competition is in many sectors less significant. Vertical disintegration occurs more often in manufacturing sectors.

The competitive pressures from globalisation which force companies to raise efficiency are not as strong in China as in many other countries. China has opened up for international trade considerably since it joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001. However, some non-tariff barriers still exist and a considerable share of companies is state-owned. This weakens competitive pressures for many Chinese enterprises and walls off markets to a certain degree.

As a consequence, the Heritage Foundation ranks China only 132nd in the world with regard to openness. Still, China is relatively open with respect to foreign trade, and it is the “export world champion”, having exported goods worth USD 1.201 bn in 2009. Further market liberalisation would increase competitive pressures and foster the development of advanced business services provided by specialised service firms. Ultimately, this would accelerate the transition into a services economy.

A third driver of structural change towards a services economy is technological progress. Just as increasing productivity in agriculture led to the establishment of an industrial society, efficiency gains in manufacturing are now resulting in a reduction of the required labour input per unit produced. Redundant labour is often able to find work in the tertiary sector; input factors are shifting from manufacturing to services. Obviously, service providers also benefit from technological change, e.g. by digitisation. However, there are only limited possibilities for the substitution of labour by capital in most service industries; there is usually more scope for automation and rationalisation in manufacturing.

This argument is reinforced by the fact that productivity gains from technological progress boost private consumption and vice versa: efficient production leads to higher wages and falling prices for goods, making them affordable for more consumers. Then, the higher demand enables economies of scale in production. In addition, wages adapt to the increased productivity in manufacturing. According to Baumol’s principle of cost disease, wages in service industries are also rising in order to maintain this sector’s attractiveness for the workforce. As this development is not backed by corresponding productivity gains, though, higher wages lead to higher prices for services. Consequently, prices for goods decline in relation to services. This change in price relations is accounted for in the calculation of the economic sectors’ shares in GDP, i.e. this accelerates structural change.

The argument of technological progress certainly applies to China as it has experienced a steep increase in productivity in recent years. Part of this has been caused by a diligent import of knowledge from abroad. The country is a net importer of technology; it spends more on royalty fees than it earns by selling technology to foreign countries. In 2007, the balance amounted to almost USD 6 bn.

China benefits from international trade and globalisation because they facilitate the importation of machinery and technology. In 2009, Chinese imports of machinery and transport equipment added up to USD 408 bn. On average, imports of these products have increased by 18% p.a. since the year 2000. Up to now, there has not been a strong drive for rationalisation in the manufacturing sector, though, or else increasing demand has offset the effects of rationalisation. In any case, during the recent upswing from 2003 to 2008 the secondary sector created 50 million jobs and outperformed the services sector in this respect (39 million); the manufacturing sector still creates most employment. This development is set to change, though. Services are more labour-intensive and thus able to absorb more of the workforce than the other economic sectors. The tartarisation process already started to speed up during the 2009 crisis when exports slumped. This is just not represented in the statistics yet. In the future, tartarisation will especially accelerate if manufacturing industries continue to focus on more complex goods production which usually is more capital-intensive and requires more supporting business services.

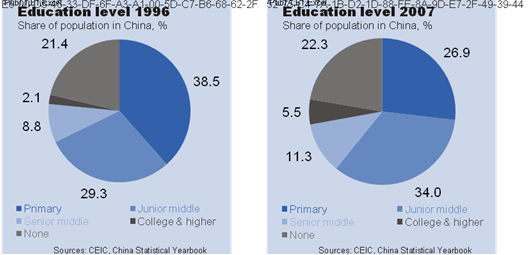

Third, rising education standards drive the transition into a services economy. On average, services are slightly more knowledge-intensive than manufacturing sectors, i.e. education levels of the workforce are higher. Naturally this does not apply to every sector and there are some service industries with low knowledge intensity, e.g. in the retail or accommodation sectors. But especially jobs in advanced business services like management consultancies or in the financial sector require a well-educated workforce.

Although the share of the Chinese population without any completed education increased slightly from 1996 to 2007, the general education level rose. This applies particularly to college and higher education: this segment’s share increased by a factor of more than 2.5. Hence, there is growing potential in China to develop advanced and knowledge-intensive services.

On the demand side, the transition into a services economy can be explained by a saturation of demand for tangible goods. Productivity gains enable companies to meet continually higher demand levels. But tangible goods frequently have an income elasticity of demand of less than one. This means that with rising income the share spent on goods declines because their marginal utility decreases. As income rises, demand increasingly focuses on services instead. The saturation levels of (consumer) services are generally higher, or else they are not sought after until a certain minimum income threshold is crossed. For this reason the tertiary sector is absorbing most of the rising per capita income and grows faster than the secondary sector in wealthy societies.

However, this applies essentially to industrial countries and not yet to emerging economies like China. Chinese consumer durables markets as a whole are not yet saturated; however, selected instances of saturation have been identified and there are large differences between coastal and inland provinces and between urban and rural regions. High incomes are concentrated in the coastal provinces. Especially in urban regions near the coast, the saturation of consumer durables markets may become an issue.

That is why the development focus is shifting from the coastal regions to interior provinces. The central government reacted to persistent regional inequality and launched the “Development of the West” programme in 2000. This initiative focuses among other things on improving the investment environment and encouraging domestic and foreign-funded business formation in inland provinces. As a result, these areas have been catching up lately. Still, demand of Chinese households is far from being saturated. What is more, with regard to the high export share of Chinese manufacturers, a saturation of the Chinese market is less of a problem than in countries which produce mainly for domestic buyers. As there is global demand for goods produced in the “factory of the world” structural change in China is not driven by saturation of demand as is the case in developed industrial economies.

Overall, the key drivers for a transition into a services-based economy are at work in China. However, so far all of these drivers are a lot weaker than e.g. in the developed economies of the West. Both in the areas of consumer as well as business services China’s potential has yet to build up. At the same time, demand for China’s export goods is still high on a global level and the manufacturing sector is growing dynamically. Nonetheless, China’s development path is similar to that of Western economies 50 years ago and it is only a matter of time until growth in manufacturing starts to weaken as global demand is not able to provide a stimulus as strong as in the boom years up to 2008. Then, competition pressures will increase and companies will have to enhance efficiency – thereby benefitting business service providers. The 2009 crisis has added momentum to this process and accelerated it. Household services are increasingly sought by consumers when living standards improve.

1b) Development of the services sector

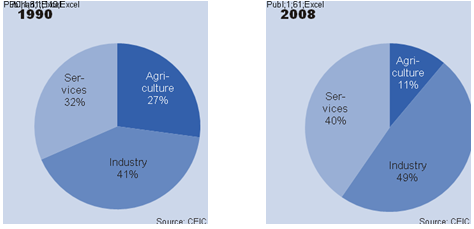

In 2008, the services sector accounted for 40% of GDP in China; it is the country’s second largest economic sector. The industrial sector generated 49% of GDP, the agricultural sector 11%. These figures changed greatly during the past 20 years. Since 1990, the services and industrial sectors have gained considerable importance at the expense of the agricultural sector.

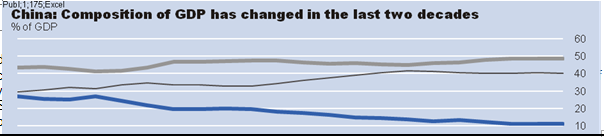

In industrial countries, the services sector’s share stands much higher at approx. 70% – in some countries such as the US, the UK or Spain it is even higher. This reflects that the drivers of structural change are not yet as strong in China as in the further developed Western countries. A closer look at China’s changing GDP composition in the course of time reveals that China’s economic structure has not evolved at a uniform pace. The change is driven partly by economic cycles, as industry and services differ in how they react to cyclical patterns. The manufacturing sector lost in importance during the late 1990s and early 2000s. During this period it was mainly services which benefited from the decline of the agricultural sector. Then again after the dotcom crisis, strong global economic growth favoured primarily the export-intensive manufacturing sector. Therefore, its share in GDP increased while the services’ share remained stable. This pattern is typical for upswings and downswings: Generally, economic crises quicken the pace of structural change, whereas the pace slows in recovery and upswing phases. Therefore, the crisis year 2009 will have increased the contribution of China’s services sector to GDP – it is simply not yet visible in the statistics.

In recent years, China has been focusing on developing the industrial sector. Growth of the services sector has for the most part not been a policy priority, but been driven first by the need to provide services to its large domestic population and second by the need to provide support functions to industrial activities. This policy focus needs to be shifted towards services in order to make China’s economy less prone to global economic downswings.

Despite its stagnating share in GDP, the services sector is growing significantly in China. The relative stagnation rather stems from considerably higher growth in the secondary sector during the last upswing. There are two main reasons for manufacturing to expand faster than services in the recent past:

First, China has opened up and become a major driver of globalisation. The country was able to attract labour-intensive industries from Western economies. Additionally, China’s history of stimulating manufacturing rather than services has aggravated this development.

Second, there has been growing domestic demand for manufactured goods. Rising incomes and living standards across the Chinese population have increased domestic demand for consumer goods. As seen in section 1a) a further rise in incomes is likely to lead to a gradual shift in consumption towards services. In China, this applies primarily to the richer coastal provinces. In contrast, this process will take time in inland provinces which find themselves at lower stages of development. Here, the importance of the industrial sector will remain significant for the time being.

1c) Outlook for Beijing’s services sector

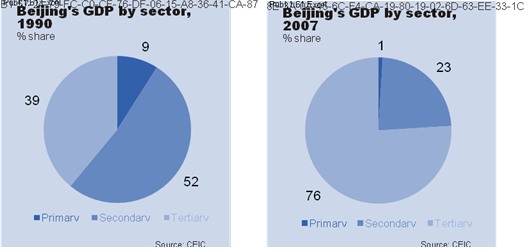

Beijing, China’s capital and administrative centre for the central government with its 16 million inhabitants, many of whom belonging to the emerging middle class, has a natural advantage in the services sector compared to other provinces. Indeed Beijing’s services sector has almost doubled its share in nominal GDP in the past two decades from 39% in 1990 to 76% in 2009, overtaking manufacturing as the largest economic sector in 1994. The nominal value of the services sector in Beijing has risen from RMB 19.5 bn in 1990 to RMB 900.5 bn in 2009.

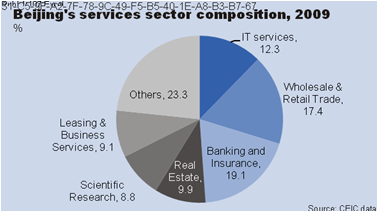

Within the services sector, the banking and insurance industry is the largest sub-sector, accounting for 19% of the services sector. The next important sub-sectors by share are wholesale and retail trade (17%), IT services (12%) and real estate (10%). Together, these four sub-sectors account for almost 60% of the total services sector value.

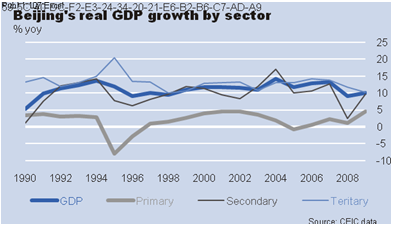

Beijing’s services sector has consistently grown by 13% p.a. since 1990, outperforming average GDP growth of 11%. The breakdown of growth rates for the services sub-sectors does not go back as far, but at least for the years from 2003-2009 available data suggests that strong double-digit growth has been achieved in most years for three out of four top sub-sectors, namely banking and insurance, wholesale and retail trade, and IT services. Other sub-sectors which have seen strong growth in the past seven years are leasing & business services (19.6%) and research (17.5%). The real estate sector has been more cyclical with growth in 2009 returning to 7% after negative growth in 2007-2008.

Sectors in focus

The performance of Beijing’s services sector has already been very impressive during the past decades. But as the Chinese economy matures, the services sector also needs to evolve to support a set of different needs in the next stage of development. In charting the way forward, there are a few service industries that deserve special attention in this regard.

—Banking and insurance

As China’s economic weight increases and the needs of consumers and businesses become more sophisticated, Beijing can spearhead future growth of the sector. Beijing’s role as the country’s banking and insurance hub benefits from the fact that all big banks (domestic & foreign) and insurance companies have headquarters or subsidiaries in Beijing in order to maintain close contact to Beijing-based regulators and supervisory institutions like the People’s Bank of China (PBC), China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC), China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and China insurance Regulatory Commissions. Beijing has been recognised by the City of London’s study on Global Financial Centres (March 2010 report) as one of the contenders for global financial centres among emerging market peers alongside Dubai, Moscow and Shanghai. In the latest Global Financial Centre Index (GFCI) ranking, Beijing came in 15th globally. In the insurance sub-index, Beijing scored well, coming in 7th place globally. Another area where Beijing was among the world’s top 10 is the banking sub-index, where the city was ranked 10th. There are many reasons that we believe will support the banking and insurance sub-sector’s outlook in the future:

1.China’s financial sector is set to become a future global force. By 2018 China is likely to account for 13% of the global financial market; over 16% of the global stock market; and over 5% of the global bond market.

2.Consumer banking has been identified as a key growth area.

3.Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) remain under-served while state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are expanding overseas. This spells good prospect for corporate banking, treasury services and investment banking.

4.China has the highest number of high net worth individuals (HNWI) among the key emerging markets, which bodes well for the private banking outlook.

5.An ageing population implies the need for asset management and insurance services.

In the future development of Beijing’s banking and insurance sector, further market opening is needed for a sustained development of China’s financial centres to make it a truly global financial centre. The fact that China is reaching out more to the world is a positive trend which will create additional business opportunities, but China’s own domestic market remains relatively closed. This, however, will require measures at the central government level.

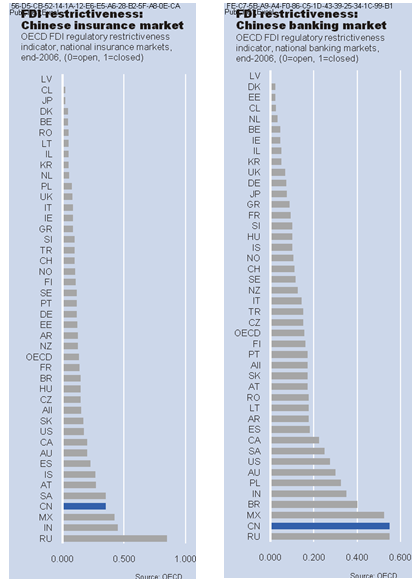

A 2007 study by the OECD shows that China can do more to open up and attract FDI in its insurance and banking sectors.

In addition to further FDI deregulation in the banking and insurance sector, continued promotion of efficient and credible domestic frameworks of the legal system and accounting standards will give a big push to improve Beijing’s situation in the Global Financial Centre ranking in the future.

—Education and research

The high density of top universities and other tertiary education institutions has contributed to Beijing’s strong performance of the services sector as they provide a pool of well-trained and well-educated talents. In this regard, China already scores well among emerging Asian peers with a tertiary enrolment ratio of 22% compared to India’s 13% but it still lags far behind developed economies such as the US (82%) and the UK (59%). This indicates that more efforts must be put into increasing tertiary enrolment for the Chinese population in terms of providing the physical facilities, expanding the capability of the institutions, as well as providing financial resources to capable applicants who may lack the financial support. Government spending on education has been concentrating more on the primary and secondary levels. This is often a reasonable and even necessary first step in boosting development because especially in these areas, positive external effects from education can be expected. However, as the Chinese economy matures and innovation defines the new frontier as a source of growth, there is a genuine need for China’s public spending to provide greater support for tertiary education as well.

Among others, the scientific research sector is depending on a constant supply of graduates. Beijing’s research sector is already strong, supported by the presence of top universities as well as public and private research institutes. In light of the urgency and growing need to cope with climate change, research in the areas of green energy and environmental protection will be in high demand, not to mention vital to the sustainable development of China. Beijing is well-placed to lead this research as it can play a role to bridge the resources between publicly-funded institutions and private corporations, for example in the area of alternative energy and emissions reduction for the auto industry or industrial use.

—Health care

The ambitious health care reform launched in April 2009 to provide a basic healthcare system widely to urban and rural residents is a clear signal from the central government that it views health care as a “public service” to the people. The central government’s initial investment plan during the first three years of RMB 850 bn is to provide the necessary support for the sector. Many areas of healthcare services will be improved such as disease prevention and control, health education, mother and infant health care, as well as mental health. Beijing’s several top hospitals and medical research facilities in leading universities can set the standard, provide training or even replicate successful models of healthcare provision to other areas in the country.

Section 2: Building up innovation capacities

China’s re-emergence as a major power in the world economy is one of the most significant developments in modern history. The overall demand levels are growing fast. The potential market volume is huge. In China, for example, hundreds of millions of people will enter the middle class in the coming decades and want to benefit from increasing welfare. China needs creative ideas to foster innovation in order to generate sustained growth and higher prosperity. Therefore faster knowledge and technology diffusion, more educational attainment in the secondary and tertiary segment, higher expenditure in R&D and more highly skilled and innovation-oriented technicians and technical workers are needed. There is no single solution, but it is beyond doubt that innovation in goods, services and processes are vital to grow economically and develop socially.

2a) Innovation – driver and adrenaline of economic success

We are surrounded by innovation: from electronic toothbrushes and music-playing, navigation-equipped mobile phones to financial products, innovation is to be found in many places and forms and is the basis for nearly all products and services. Without innovation, there is no progress. Innovation is a key economic factor, generating growth, employment and prosperity. Innovation also makes a major contribution towards ensuring competitiveness.

Innovation process as a black box

A wide range of definitions of innovation can be found in the scientific and policy-oriented literature. The European Union, for example, defines innovation as the successful production, assimilation and exploitation of novelty in the economic and social spheres. The term is commonly used to describe new ideas and inventions and their commercial application. Thus, innovation ranges from the idea right down to the marketable product, with the path to completion defined as the innovation process. The innovation process is multi-faceted and can be more accurately compared with the complex network of roads in a city than a straight motorway that leads directly to the destination: Ideas often do not lead straight to the desired outcome. On the contrary, they have to be reconsidered, readjusted and revised. Accordingly, feedback or loops form part of the innovation process, which itself also undergoes permanent change. To measure or estimate innovation for a region or an entire economy appears to be virtually impossible.

The innovation process – from the conception of the idea to the finished product

Besides, innovation has many guises. Innovation can be found in new technologies, products, services, types of organisations, process techniques as well as production or process methods. Innovation is influenced by societal and social changes, as well as economic policy in particular, and is in turn a trigger for organisational innovation. It is therefore more than a simple technical solution for specific problems. The following figure provides a simplified illustration of the basic structure of an innovation process. Key elements are the individual phases of the innovation process that are required for the transformation of ideas into marketable products and services. The diagram is based on standard process models and enhances these with additional dimensions containing potential (upstream) input and (downstream) output indicators.

The innovation process begins with creative ideas and first drafts which sourced by humans. The following individual but closely linked innovation phases, represent sub-processes from the organisational business units such as development, purchasing, production, sales and all upstream and downstream links with suppliers, official bodies, research institutes, competitors and clients. Test or pilot phases designed to provide indicators of success and customer acceptance are also standard elements of the process.

The innovation process consists of a number of sub-processes, some of which are consciously managed and operate informally, while others occur spontaneously. Accordingly, feedback and interdependencies of differing frequency and intensity do occur between the individual phases. Feedback can, for example, come from ideas which, in the end, are not implemented as planned within individual sub-processes during the creation of the product or service. In this case, the steps in the preceding phases have to be revisited and, where necessary, modified and/or changed, or the idea may even have to be completely abandoned.

Who are the players?

Increasing global interconnectedness means that a successful innovation process is reliant on active collaboration between business, science, politics, society and culture. It is therefore inadequate to focus solely on companies, although they do perform a key role in the innovation process. They often initiate and implement ideas, but there are far more factors and decision-makers involved in the innovation process who share the responsibility for fundamental activities. They include:

•Research and science, which develop new methods and methodologies

•The education sector, which produces the required highly qualified personnel

•Investors, who provide the necessary (venture) capital

•Lawmakers who create an innovation-friendly environment

•Consumers themselves, whose consumption habits prompt product developments from manufacturers or who even become involved in the development process themselves (interactively).

Participants from the ranks of education, politics, science, entrepreneurship, society and culture enter the innovation process in different combinations and they collaborate with varying intensity. At every single step in the process, the participants make contributions that impact on the innovation process.

But how do international surveys (e.g. Global Innovation Index, European Innovation Scoreboard) rate the innovation performance of a country, when the innovation process is extremely complex, in transparent and cannot be measured directly?

The scientists of these studies look at variables that can provide indications of a country’s innovation performance via the inputs and outputs of the innovation process. The input-side indicators used are innovation drivers which provide mutually dependent stimulations of the innovation process. Examples of input indicators include R&D spending, the risk appetite of individuals, the standard of technical equipment at companies (such as those with broadband connections), or the access to funding (in particular venture capital). Other particularly important input indicators are education spending, the number of graduates or the share of the population that has completed vocational training.

Output indicators are variables that characterise the success of the innovation process such as export shares, especially in the case of technology and knowledge-intensive segments. Patents can also be selected as output variables of the innovation process, as can the number of papers published in academic journals or royalty fees. Sales figures can also help to draw conclusions about the marketability of new products and services.

2b) China’s innovation performance

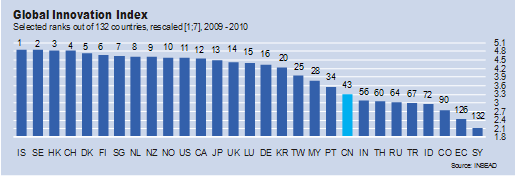

According to the Global Innovation Index 2009-2010 (GII) computed by INSEAD, China ranked 43rd out of 132 countries. Seven pillars, making a distinction between five input and two output indicators, help to determine the status quo in a country. The input pillars include institutions, human capacity, ICT and uptake of infrastructure, market sophistication and business sophistication. The input measures the capacity of a country to create new ideas and transform them into innovative products and services. The output indicators include (scientific) knowledge on the one hand; and creative output and social welfare on the other, with the implicit assumption that the use of knowledge stimulates (global) competition and thus leads to higher prosperity.

This ranking shows that China still lags behind in terms of innovation activity. Since the GII ranking includes countries of all development stages, it is, however, noteworthy that China is among the upper third of all countries with most of the economies ahead of China being developed economies. This position reflects China’s current development stage: it is still considered as an emerging economy but on the edge of being a developed one. This imparity is also mirrored in the discrepancy between coastal and inner provinces. China has caught up over the past years but needs to continue this process in order to become competitive with developed economies. Beijing’s innovation performance is stronger than China`s as a whole. Consequently, if assessed individually, Beijing would be ranked higher than the 43rd place of China.

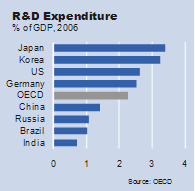

Several indicators such as R&D expenditure, graduates in science and engineering (S&E) and patent applications can shed light on China’s performance in innovation activities. Regarding R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP, China ranks below the OECD average but takes the lead among the BRIC countries. As China appears to recognise that it is lagging behind developed economies in this respect, Chinese state-owned enterprises have been acquiring overseas companies in order to access technology, R&D facilities and personnel as they build up more capacities at home.

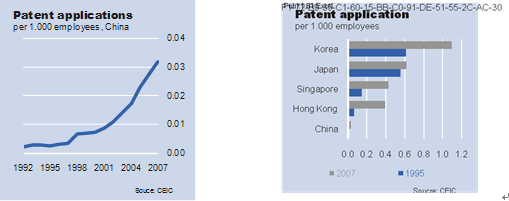

With respect to patent applications in relation to employees, China has experienced a considerable increase from 1995 to 2007. Within this time frame, China has realised an increase in patent applications of more than 1,000%, followed by Hong Kong with an increase of 480% while Japan “only” realised an increase of 11%. Of course, level effects play a decisive role here. Nonetheless, the rapid increase suggests that more firms engage in innovation activities successfully. Chinese companies will therefore become more competitive on global markets. With regard to the fact that China only began its opening and reform process at the end of the 1980s, an average annual increase in patent applications of 22% is quite an achievement. Additionally, Singapore and Hong Kong are city states while China has large geographic dimensions. Thus, a far larger share of the population works in traditional sectors like agriculture where engagement in innovative activity is much lower. Compared to its regional peers (e.g. Korea, Japan), however, China still has a long way ahead until it reaches a level comparable to that of developed economies.

According to cross-regional comparisons, Beijing is one of the most innovative regions within China. Beijing’s R&D expenditure ranks far above China’s average. Even though there has been a slight decline since 2004, Beijing’s R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP still equals about three times China’s average expenditure.

Accordingly, Beijing can be considered one of China’s most intensive research areas and as an innovation leader. In terms of S&E graduates as a share of the population, Beijing has experienced a sharp increase in the past decade. More and more high-skilled engineers who can potentially enhance Beijing’s innovation activity are entering the Chinese labour market. On a nation-wide basis this trend is confirmed by the IMD ranking on qualified engineers in which China moved from rank 58 to 52 within the five years from 2004 to 2009. Beijing and Shanghai are not only the two largest cities with the most important universities within China but also the centres of innovation. With Beijing Daxue (Beijing University) and Qinghua Daxue (Tsinghua University) Beijing even outperforms Shanghai in this respect having about 10,000 more graduates in S&E. With its good access to infrastructure as well as a large number of graduates, Beijing is thus a very attractive location for highly innovative firms. This development is backed by the fact that China has increasingly more available skilled workers. In the IMD ranking for the availability of skilled labour China moved up the ladder from rank 55 to 39 within the five years up to 2009.

2c) Improving innovation capability

Collaboration as an instrument to foster innovation

Innovation involves dimensions from both the supply side and the demand side. Today, hardly any innovation is produced by a single person. Networks and different forms of collaboration are required to bundle innovative resources. Together all participants spin an innovation web that is characterised by creative and interactive (often only temporary) collaboration. Every single participant thus possesses unique, special, situation-based or local knowledge that improves the entire innovation process by bringing together fragmented knowledge. Collaboration becomes faster, more specialised and more productive. The result is more efficient resource deployment, cost-saving synergy effects and interdisciplinary. Moreover, collaboration enables entrepreneurial risk to be diversified.

Interdisciplinary collaboration

The linkages between different sectors result in more frequent changing of sides between the individual process dimensions by personnel. Interdisciplinary cooperation leads to the respective decision-makers understanding and learning to apply methods and approaches from an alternative perspective. This learning effect boosts the problem-solving potential of all those involved. The better the individual player's professional knowledge is, the greater the cooperation's integration, transparency and trust is, and the higher the quality of the national innovation system is.

The term “National Innovation System” is defined as the network of institutions in the public and private sector whose activities and interaction initiate, import and diffuse new technologies.

requires increased management effort

Collaborative working arrangements, however, require increased coordination and organisational input. Necessary evaluations of the partial process results, modern management styles, non-hierarchical communication as well as a genuinely implemented feedback culture and/or “innovation from below” are helpful qualities for successful interdisciplinary collaboration.

Despite their collaboration those involved can, for example, possess differing project-based knowledge and also be at differing stages in achieving their objectives. Opening up the innovation processes and collaborating with stakeholders speed up the learning effects. The feedback loop in particular is an especially effective process instrument. The entire innovation process requires an active feedback culture across all sub-processes due to the embedded feedback and loops in order to continually optimise by eradicating errors.

Core element of the innovation process remains knowledge

Besides curiosity and the joy of breaking new ground, the origins of every innovation also lie in the insatiable needs of mankind and in the resulting ideas on how to satisfy them. Spontaneity is also a source of innovation. An apposite quote from Wilhelm Busch (German caricaturist, painter and poet) in this respect is: “Each desire once fulfilled immediately begets another.” Ideas are based on the knowledge and the creative potential of specific individuals. Consolidating fragmented sources of knowledge is thus one of the key areas of the innovation process.

Knowledge generation stimulates technological progress and is increasingly shaping the structure of modern economies. According to modern growth theory, technological progress is primarily the product of the skills and/or the training of the workforce as well as research and development (R&D) and its diffusion.

“Knowledge commons”

Unlike other factors of production such as capital, raw materials or labour, knowledge possesses an economically important property: the use of knowledge is non-competitive in its impact, i.e. the use of the knowledge of one person does not preclude its simultaneous use by a second or third person. If physical products are exchanged, then the owners of these objects change as well. If, however, ideas are exchanged, each party has two ideas after the exchange has been concluded. This could be one of the reasons why the growth of leading economies in the past decades has been mainly attributable to increased knowledge and its increasing dissemination.

Innovation processes are subject to constant change

Innovation processes are not static but are the outcome of the changing approaches adopted by the parties involved. The environment in which the innovation process occurs is also subject to constant change that can directly influence each participant and compel him to adapt. Structural change in the Chinese economy is broadly characterized by a shift from agriculture to services, with shares that are still significantly larger and smaller, respectively, than those of OECD countries. Unlike some emerging economies, China has not started to de-industrialize but has strengthened its manufacturing base. This is a reference not only to short-term cyclical fluctuations but in particular to long-term structural changes. Innovation processes are thus subject to constant change which can be characterized roughly by the following developments:

Probably the most economically influential trend remains the increasing global integration between the fields of information, technology, capital (direct investment), human resources as well as goods and services, with the pace of technological progress accelerating, the importance of the service economy growing and the volume of digital and virtual goods, services, processes and business models increasing. Especially the emerging countries will undoubtedly make a growing contribution to breakthrough innovations in the digital world.

Furthermore, the speeding-up of the innovation process (shrinking product life cycles and shorter reaction times) in recent years points to a growing tendency among participants towards greater collaboration and thus the opening up of innovation processes.

An OECD survey of the internationalisation of private-sector research and development projects also showed that most collaborative ventures in the scientific and technological sphere were the result of initiatives and contacts established by individual researchers and companies, regardless of political strategies and initiatives. The growing importance of intellectual capital, lifelong learning, greater citizen sovereignty as well as demographic change is influencing the innovation process via the individual as a bearer of knowledge and a source of ideas. This means that there are some companies with a small number of employees and few tangible assets whose market capitalisation is higher – in relative terms – than that of other companies with more employees and bigger balance sheets. Knowledge-intensive and knowledge-driven companies often have just one money-making idea whose implementation exists in the minds of the employees.

Conclusion

The need to diversify China’s sources of growth has become clear, not least against the backdrop of a potentially weaker global demand. Developing China’s services sector and fostering innovation would greatly contribute to that aim.

A stronger policy priority for the services sector would enforce the drivers of tartarisation and accelerate the transition into a services economy. Beijing already displays a high share of value-added of the services sector with an exceptionally large financial sector. Thus, Beijing is qualified to play a key role in spearheading the future growth of the services sector in China. In terms of innovation, China still lags behind developed economies. But the country is catching up fast and accessing technology e.g. by acquiring overseas companies. Like in the case of services, Beijing plays a major role as innovation leader in China. Taken together, the prospects for Beijing as a driver of the “new growth model” in China look bright. It takes now perseverance in the policies already put in place and further fruitful cooperation between policymakers, Chinese enterprises and foreign companies operating in China to achieve that goal.

主办:中国国际贸易促进委员会北京市分会

建设运维:北京市贸促会信息中心

京ICP证12017809号-3 | 京公网安备100102000689-3号