所在位置:首页 > 贸促动态 > 市长国际企业家顾问会议 > 往届回顾 > 第九届顾问报告 > 正文

Building Beijing:Creating an innovative world-class metropolis for the 21st century

2012年05月23日 来源:中国国际贸易促进委员会北京市分会

We are honoured once again to be invited to join the distinguished group at the International Business Leaders Advisory Council (IBLAC) and to submit this perspective. In previous years we have used the forum to present our research results into the challenges and opportunities for Beijing and China as a whole as the country seeks to implement a balanced, sustainable and inclusive growth model. Our previous submissions covered topics such as stimulating growth of Beijing’s creative industries, understanding China’s urbanisation path in the next 20 years and its implications for Beijing. This year we wish to expand on our urbanisation work with a proposal for the establishment of a new institution: The Urban China Institute. We feel the creation of such an entity could serve as a catalyst for Beijing’s transformation into a true “world city”. We believe that by helping to accelerate that transformation in Beijing, the Urban China Institute could create a model for other large cities – not just in China, but elsewhere in the world.

The document is divided into four parts:

1.Context: The historic success of urbanisation in China and Beijing;

2.Challenges and opportunities for Beijing in the next 20 years;

3.Four imperatives required to build Beijing into a world-class innovative metropolis for the 21st century; and

4.Immediate implications: The Urban China Institute.

1. CONTEXT: HISTORIC SUCCESS

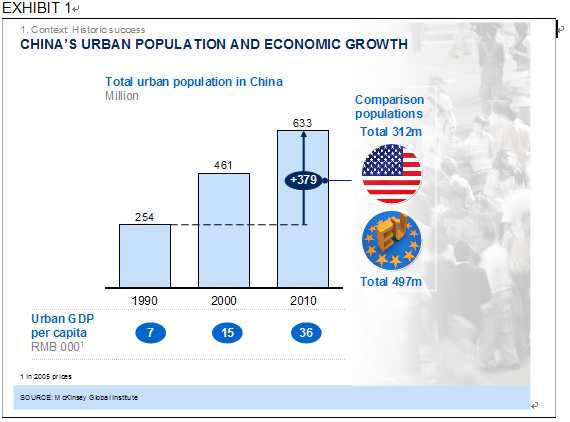

Over the last few decades China’s urbanisation has been a tremendous success. Since 1990, China’s cities have absorbed nearly 400 million additional residents and achieved a five-fold gain in urban GDP per capita (Exhibit 1).

As their populations grow, cities like Beijing have developed into economic powerhouses, exerting influence both locally and internationally. Beijing’s local GDP has grown at an average annual rate of 13% from around 100 billion Renminbi in 1990 to above 1.3 trillion Renminbi today, outpacing both China’s national economy and other developing metropolises like Istanbul. Beijing is now home to 26 Fortune 500 companies; only Tokyo and Paris boast a higher concentration of Fortune 500 headquarters. Beyond economic development, Beijing has emerged as a global focal point: host of high-profile international events like the Beijing Olympics and home to some of the most advanced architecture and infrastructure projects in the world.

2. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

And yet, over the next two decades, Beijing must surmount two inter-related challenges. First, it must maintain the current pace of urbanisation, taking in millions of additional residents, and building the homes, schools, hospitals, utilities, roads, mass transit networks and other infrastructure needed to accommodate them. Second, it must keep pace with the aspirations of China’s leaders and citizens for continued dramatic improvements to the quality of urban life.

Urbanisation creates substantial pressures on resources. By 2030, the share of migrants as a percentage of China’s urban population is expected to rise to 40% – up from 25% in 2010. Oil consumption in China’s cities will triple, even if current policy goals are met. In the absence of new policies, four of China’s ten main water regions are projected to experience severe shortages within the next two decades.

Chinese city-dwellers are a demanding constituency. Consider this – 97% of China’s urban residents say they expect their child to attend university. Making that dream a reality implies a four-fold increase in current university enrolment. One in ten urban residents say they plan to buy a car in the next two years; on current trends, urban passenger cars could increase six-fold to 180m by 2030.

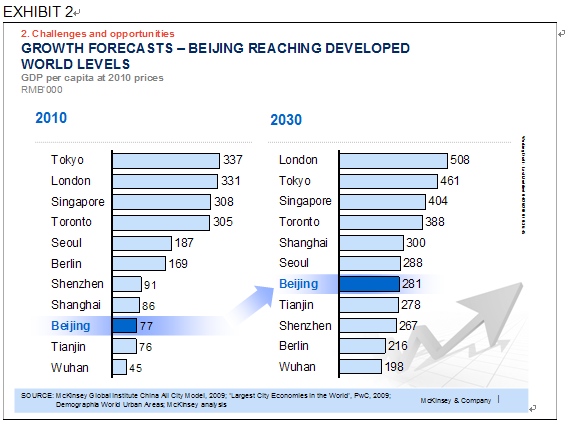

Like a cyclist who must speed forward to maintain balance, China’s cities must continue to grow at a rapid rate to match the aspirations of their citizens. Beijing is expected to approach the GDP per capita of the world’s wealthiest cities by 2030 (Exhibit 2). But, as China’s leaders have often warned, it is unclear that today’s high growth rates can be sustainable in the absence of significant changes in China’s current economic model.

Even so, we believe the very scale of the challenges faced by China’s cities is a source of opportunity. China’s cities cannot maintain equilibrium by “muddling through” or tinkering with the status quo. They confront a strict imperative for dramatic change. Their only hope is to “leapfrog” into a new stage of urban development. Our view is that Beijing is the ideal location for demonstrating new forms of urban development that might serve as models for other developing metropolises in India, Southeast Asia, South America and Africa.

3. FOUR IMPERATIVES REQUIRED TO BUILD BEIJING INTO A WORLD-CLASS INNOVATIVE METROPOLIS FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

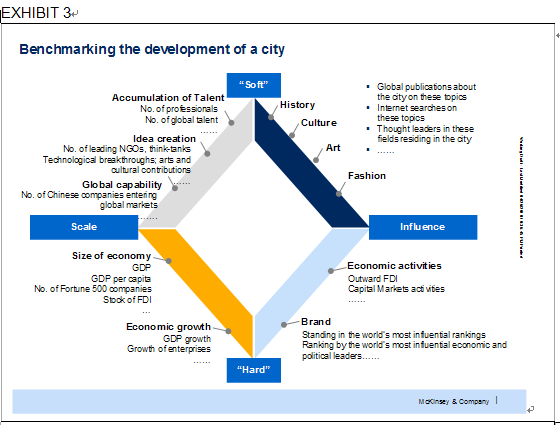

We believe the time has come for Beijing to move to the next horizon of urbanisation – evolving into a world-class “innovative metropolis”. Economic performance is important, but cities must also be evaluated by other factors conducive to long-term development and the well-being of their citizens.

The exhibit below suggests a more useful framework for evaluating urban development (Exhibit 3). It is important to measure both the scale and influence of urban development and to consider both “hard” measures of economic development and “soft” measures of contribution to global thought, culture and arts.

We draw a distinction between “world cities” and “world class cities”. The latter designation suggests outward performance, whereas the former reflects a city’s interior qualities. To become a “world city”, Beijing should think about areas in which it will lead, shape and change the world and not just about how it will catch up on measures of wealth and infrastructure.

We see four things Beijing can do to advance its bid for “world city” status:

A. Create an innovative entrepreneurial environment;

B. Broaden the talent base;

C. Shape sustainability innovations; and

D. Develop new public services financing and regulatory models.

A) Creating an innovative, entrepreneurial environment

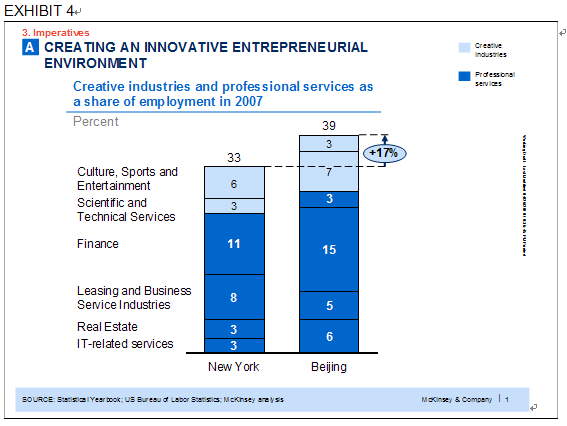

Over the past decade, Beijing’s economy has grown quickly as large corporations and state-owned enterprises gained scale and foreign investment poured in. Foreign direct investment now accounts for 4% of Beijing’s GDP. The city ranks 8th in China in attracting foreign investment. Preferential policies to stimulate growth in creative and advanced service industries have produced visible results. In 2009, the contribution creative industries made to Beijing’s economy rose to 13% – up 10% from a year earlier. In fact, the percentage of Beijing’s workforce engaged in creative industries and professional services resembles that of its global peers (Exhibit 4).

But Beijing’s record in promoting entrepreneurialism and innovation is uneven. For instance, the city’s innovative capacity, as measured by number of patents filed, gained 26% from 1997 to 2006. But relative to global peers, Beijing remains a laggard in innovation, with only 944 patents filed in 2006 versus 6408 filed in New York. Innovation will grow from entrepreneurs and small businesses above all. Beijing must move beyond its current patchwork of small business initiatives to create a cohesive, business-friendly environment for innovators and entrepreneurs.

Beijing’s efforts to foster such an environment should proceed on these three fronts:

■Unleashing entrepreneurs: Beijing should expand services to small business (e.g., establish a Small Business Administration for China), ease regulations for setting up a business and improve Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) access to capital. Launching a new business in Beijing is far too difficult and time consuming. Our research finds that in 2008, establishing a new business required an average of 37 compared to just five days in Singapore. SMEs in China received only 22% of loans, compared to 45% for SMEs in South Korea. South Korea offers a useful case study in how government can support SMEs. South Korea’s Small and Medium Business Administration provides comprehensive support (e.g., global marketing campaigns, investment promotions), making SMEs a crucial part of Korea’s recovery after the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and 1998.

■Build platforms for cross-fertilisation: Beijing should create institutions and organisations that conduct research in multiple sectors and apply ideas across different fields. The California Institute for Science and Innovation draws together the public and private sectors to pursue research critical to the growth of the state’s economy (e.g., software development, communication technology). World-class, interdisciplinary design institutes (e.g., the Royal College of Art in London, Musashino Art University in Tokyo) function in a similar manner. Beijing’s nearest equivalent to these institutions – the Academy of Arts & Design at Tsinghua University and the Beijing Industrial University – claim only 1,560 students – far fewer than the 5,650 in London and 12,465 in Tokyo.

■Develop market opportunities: Market forces, consumer feedback and competition are key motivators for innovation. In Europe, outward FDI by firms local to a region – rather than inward FDI by foreign firms – is the strongest indicator of innovation in a region. More specifically, Beijing can support its local companies globally by:

–Sponsoring trade shows: The Singapore International Chamber of Commerce, which assists members with regional and global expansion by connecting them to a network of ambassadors and trade commissioners from many countries, offers a possible model.

–Providing “soft” infrastructure needed to facilitate expansion: The SPRING agency in Singapore provides technical assistance in developing exports, supporting SMEs in obtaining the financing, capabilities and other factors they require in order to expand successfully.

Many of these initiatives will be most effectively implemented as partnerships including government, leading companies and universities. For companies, such partnerships offer an opportunity both to boost their own innovative capacity as well as to develop new markets.

B) Broaden the talent base

While Beijing’s overall economy (in GDP term) has grown quickly at 13% per year over the past 20 years, disposable income per capita has only grown at 8% per year and the current level is still only 25% of Singapore’s level. The benefits of economic development have yet to be fully translated into improved quality of life for Beijing residents.

The overall talent level in Beijing depends heavily on continuous education and constant improvement in vocational skill sets. While it is important to support the development of world-class institutions, a wider spectrum of the citizens will benefit from a focus on upgrading capabilities on a broader scale (e.g., in polytechnics).

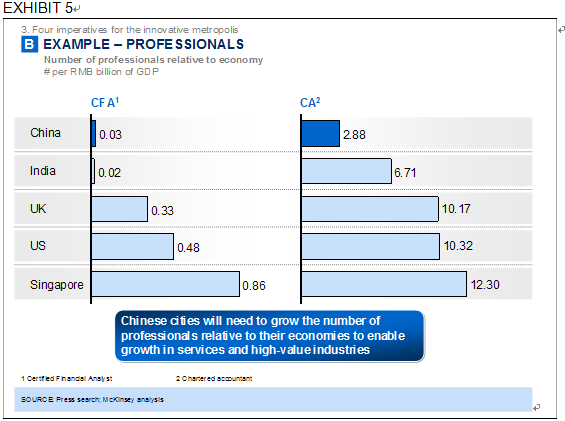

A recent survey of human resource managers found that as few as10% of Chinese graduates are ready for globally competitive companies and the number of professionals relative to the economy is smaller even than in India today. At the same time, China’s education system is of unparalleled scale – with the total number of students exceeding 300 million or close to the population of the US – which both gives the potential for tremendous innovation from so many local institutions, but also the challenge of finding solutions that will work at scale.

To address this, Beijing can pursue one specific and three general areas of focus:

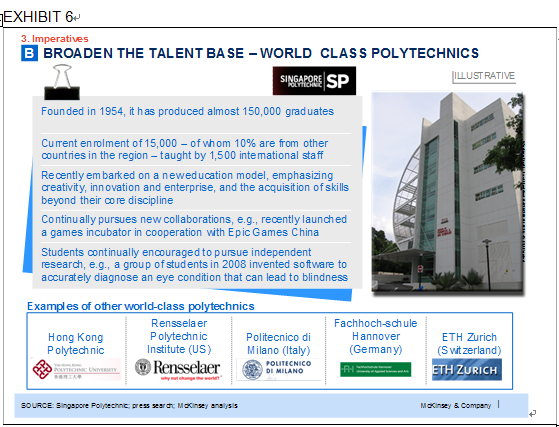

■Vocational colleges, especially polytechnics – Polytechnics focus on specialised and on-the-job training for high-skill occupations and equip students with the skills and tools that directly reflect labour market needs (see Exhibit 6 for examples of world class polytechnics). These colleges will need to be seen not as second-class universities, but as specialised colleges for training skilled workers. Hence a strong link to industry will be a key to the success of these institutions. Moreover, private education must also be part of the answer to this challenge (China’s 11th five-year plan already emphasised the importance of these fields).

■Encourage local innovation – within the national framework, further encourage schools and colleges to try new partnerships and methods. Many of Beijing’s schools have already started to organise joint programmes with foreign universities or private corporations and already enjoy significant autonomy in management matters such as teacher productivity pay. Selected schools could be given the autonomy to innovate in other matters, such as improving teaching methods, conducting more team exercises and devising curricula to unleash students’ creativity. Successful innovations in Beijing could then be scaled up and replicated in other leading cities in the country.

■Increase collaboration and linkages – both public-private partnerships and with international institutions – as some cities in China have already begun to do this by working with private companies to upgrade the technical quality of their vocational colleges. Internationally, private companies in Finland can apply to be partners in vocational instruction, in which case students receive job-based training such as internships that count as a credit towards their graduation. By doing so, students not only graduate with practical skills and job experience, but colleges can expand despite funding and teacher constraints.

■Focus resources on teacher quality – Singapore has had enormous success in attracting high-quality teachers. Many experts credit the city-state’s superior teachers for the consistently high scores earned by Singaporean students on international achievement tests. Notably, Singapore’s students get top marks on such tests even though Singapore spends far less than OECD average on education (15% of GDP per capita on each student in Singapore versus the OECD average of 20% GDP per capita). The key to Singapore’s teacher recruiting effort is a rigorous selection process for teacher training courses (the programme accepts only 20% of those who apply) coupled with high employment security for those who pass (90% of graduates from the training programme are offered jobs). The result is that in Singapore teaching is perceived as both an exclusive and lucrative profession.

Human capital will be crucial to the next stage of urban growth which focuses less on improving “hardware”, but rather on enhancing social well-being. Beijing can address this requirement by addressing the broad base of educational students via innovation, collaboration and teacher quality.

C) Shape sustainability innovation by introducing private sector investments

Chinese cities need to invest heavily to boost energy and water productivity. We estimate China will need to invest almost RMB 2.5 trillion from 2010 to 2030 to realise its carbon abatement potential. Beijing is of no exception. In fact, while Beijing has come a long way by lowering its energy consumption per unit of GDP from 0.64ton sce / thousand USD in 2005 to 0.43ton sce / thousand USD in 2009, this is still more than 60% higher than its global peers such as Singapore.

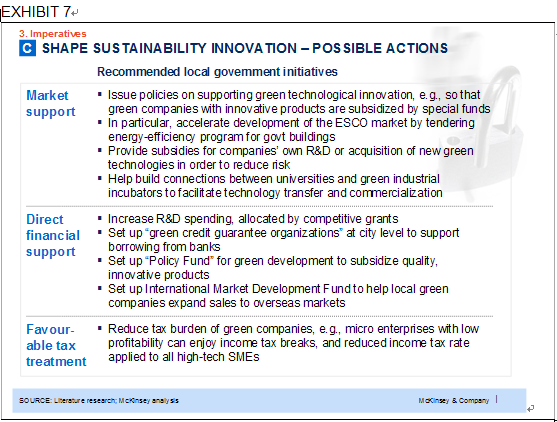

While many cities still believe “green” and “GDP” are opposing goals, “sustainability” initiatives can in fact achieve both – unlocking the private sector’s capacity for innovation. There is little alternative in China today to government investment – while China accounted for 7.5% of global clean energy investment in 2008, it attracted less than 1.5% of the sector’s venture capital. We believe the following four approaches to unlocking private innovation (Exhibit 7) hold particular promise:

■Use procurement to “make the market” by adopting buying policies more open to new suppliers and being early adopters, and giving sustainable products priority in purchasing decisions. Beijing could turbo-charge the development of the Energy Service Company (ESCO) market by ambitious programmes to retrofit government buildings.

■Take bold leaps in regulation and standards – e.g., outlawing “sick buildings”. Consistent enforcement of sustainability regulations would create more confidence among entrepreneurs and financial institutions about the prospects for their products, and therefore unlock the capital for expansion at scale.

■Encourage private finance for sustainability through, for example, “green credit” guarantee funds. Currently only 1% of commercial loans in China are going to green projects, while private green retrofitting is difficult to finance. Several European countries have initiated finance plans to provide loans for residents wishing to make their homes more energy efficient.

■Support start-ups with infrastructure as in some German cities, universities provide start-ups with access to expensive equipment – e.g., for lab testing in order to facilitate their growth (for example, as in the University of Bochum, the Chemnitz Technology Centre and the University of Bielefeld in Germany – among others).

A dedicated “sustainability desk” could tie these initiatives together, with an overall mission to rapidly grow sustainable industries in the city. Such a unit would aim to reconcile sustainability and growth through, for example, increasing the global awareness of a city’s market for sustainable products, thereby attracting new investment while promoting green businesses already existing in the city. It would also coordinate across government departments to ensure the thorough execution of the sustainability agenda.

D) Develop new public services financing and regulatory models

The initiatives described above will require substantial municipal investment. Infrastructure and other public services will require significant funding. In 2009, Beijing already had a total of 228km of urban transit routes under operation and this is going to more than double by 2015.

To meet the challenge of funding increasing public services spending without raising tax burdens, the Government should consider new financing and regulatory models:

■Adopting best-practice commercial models: Beijing already has experimented with new

infrastructure operating models. By introducing the MTR of Hong Kong to operate and maintain Beijing Metro Line 4, the city’s incumbent infrastructure operator has gained business perspectives on optimising operations and making impactful investments, similar thinking could be employed in other public services.

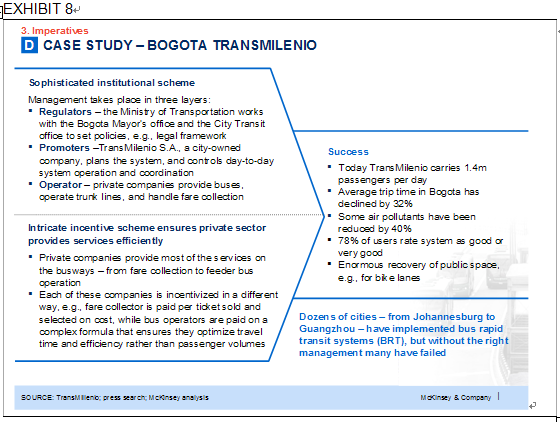

■Aligning operators’ incentives with citizens’ needs: in order to, for example, maximise transport mode integration and minimise commuter time while ensuring adequate returns. In Bogota’s bus rapid transit system, sophisticated institutional arrangements and incentives mean the system swiftly handles 1.4m passengers per day while continuing to expand and this has been much more successful than similar systems elsewhere (Exhibit 8).

At the same time markets for products that support infrastructure management will grow rapidly, for example, in advanced software for managing rail, bus and congestion pricing systems. As with sustainability, the municipal government could play a critical role in creating a market by setting and enforcing standards.

4. THE CATALYST: URBAN CHINA INSTITUTE

The agenda we propose will not be easy. However, China is already shifting, and its leaders have made a call from the top for a new direction. The goals set by China’s leaders are achievable using existing and foreseeable technologies. But knowledge of those technologies– and an understanding of how to implement them– lags far behind.

Over the last 20 years China’s city leaders have become very adept at implementing an investment-centric growth model. Now new capabilities and thinking will be needed for the new model of more balanced growth that has been articulated by China’s leaders. These capabilities must be developed quickly and deliberately.

To support structural adjustment in Chinese cities, we propose Beijing become the base for a public-private think tank– the Urban China Institute. The mission of this new entity will be to act as a catalyst for the next horizon of China’s urbanisation and to support China’s cities as they innovate. To that end, it will provide:

■Solutions – fact-based, objective analyses of the challenges and options available to urban leaders, and evaluations of domestic and global best practices in project design, development and execution.

■Talent – a home for China’s leading domestic and international urban thinkers and professionals, and a magnet for the best global thinkers.

■Dialogue – a convenor of China’s leading national, provincial and local dialogues on urban issues to facilitate the spread of new ideas and emerging best practices.

■Partnership – a support for urban leaders in forming inter-city and public-private partnerships nationally and globally.

By combining these aims, the Institute will also be able to pursue knowledge initiatives at scale– fact-based, objective analyses of options available to urban leaders across an enormous variety of conditions, with the goal of unearthing solutions that can be made to work across hundreds of cities. Indeed, as the nation’s capital where representatives from different cities and provinces most frequently come together and interact, Beijing is in a unique position to be at the centre of this effort.

The Institute would join together government agencies, local and international corporations, academics and multi-lateral organisations in a common vision – to be a catalyst for the next horizon of China’s urbanisation and to support China’s cities in seizing their opportunity to innovate for the world. Relevant agencies would be key stakeholders. The Institute should draw on examples from China and abroad. It should serve as a bridge between research and new technology on the one hand, and the agendas, priorities and decision making of policy makers on the other.

While China’s situation will make the Institute unique as well, it can also draw on an increasing number of other urban-focused institutes globally. The oldest is the Urban Institute (Exhibit 9), established in the US in 1968 and a key contributor to policy debates there. Recent years have seen a rapid increase in the number of such institutes– another was founded in Australia in 1993 and since 2005 yet another three have been initiated– two in the UK and one in Singapore. These institutes pursue different focus areas – e.g., the Urban Institute is research-focused, whereas the Centre for Liveable Cities in Singapore spends more time on events and training. However, all are alike in drawing on a wide range of funding sources and research partners, and bridging the gap between policies and ideas for action.

Beijing has a unique opportunity to forge a new model of urbanisation that can inspire cities in other developing countries. We hope the Institute would itself become a model for urban think tanks around the world. The moment for action is now. Relative to the scale of the challenges Beijing faces, the investment required to be this new catalyst would be small. The potential benefits are significant and lasting.

We would be honoured to support the development and agenda of such an institution.

主办:中国国际贸易促进委员会北京市分会

建设运维:北京市贸促会信息中心

京ICP证12017809号-3 | 京公网安备100102000689-3号